Updated

North Africa and the Birth of the US Navy – David S. Bloom

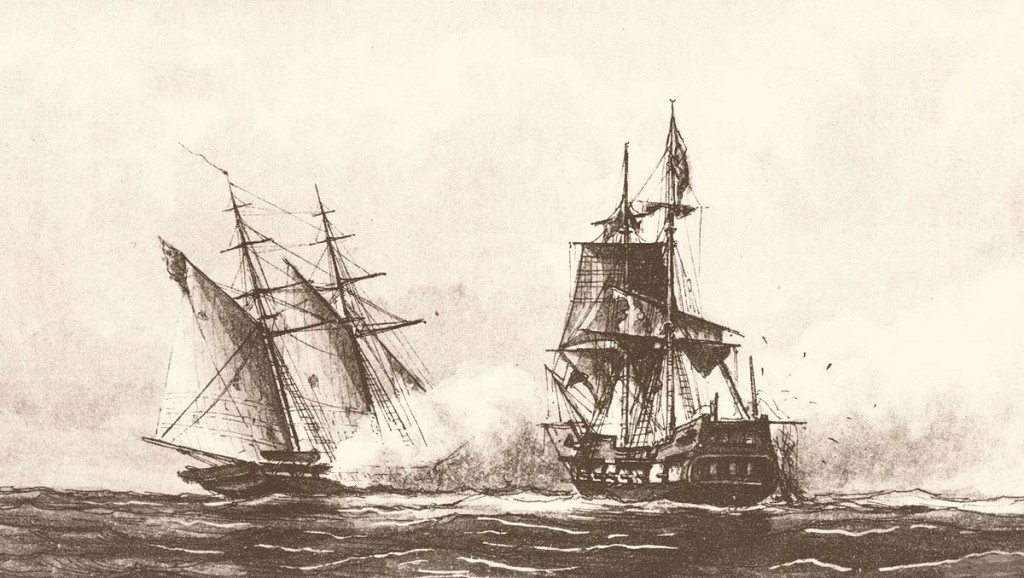

USS Enterprise fighting the Tripolitan polacca Tripoli by William Bainbridge Hoff, 1878. Photo: Wikipedia Commons

David S. Bloom

August 23, 2017

Many people already know that Morocco was the first country to recognize the United States, on December 20, 1777, while it was still in the throes of the revolutionary war. Less well known is the fact that this act of recognition was but a small chapter in the long and complicated story of one of America’s first global entanglements–which ultimately led to the birth of the US Navy. As the fledgling United States tried to cope with complicated relations with the European powers, it also had to contend with Mediterranean pirates from Africa’s northern coast as it attempted to emerge as a prominent global trader—a conflict that eventually led to the Barbary wars.

State-supported piracy was rife along Africa’s northern coast and many European powers found it expedient to simply pay tribute to the Barbary States (which included political entities based in modern-day Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya) rather than commit military resources to protect their ships. Before independence, vessels from the colonial states were protected by British treaties with the Barbary States and by the British navy.

Laureys a Castro – A Sea Fight with Barbary Corsairs. Photo: Wikipedia Commons

After the US became independent, however, “British diplomats were quick to inform the Barbary States that US ships were open to attack,” and warships from Algiers were “encouraged” to seize American merchant ships and hold their crews hostage. These attacks were meant to elicit negotiations and eventual tribute payments from the US, which quickly established a commission—led by Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and Thomas Jefferson—to negotiate treaties with Morocco, Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli.

Meanwhile, the Emperor of Morocco, Sidi Mohammed had “learned about the American colonies’ struggle for independence through the French consul assigned to Morocco and via European newspapers.” He is said to have admired their success in fighting the British, whom he reportedly disliked, and on December 20, 1777, he included them on a list of countries welcome in Moroccan ports and thereby recognizing the newly independent United States as a sovereign country. The US was slow to respond to this overture, however, as it was busy fighting its revolutionary war and devoting its foreign efforts to finding support from the major European powers.

It wasn’t until 1787 that the US and Morocco negotiated a rare treaty that obligated no US tribute payments. At the end of 1789, President George Washington penned a letter to the Emperor of Morocco, which he called “our great and magnanimous Friend,” to express thanks for Morocco’s successful engagement with the US:

“The Encouragement which your Majesty has been pleased, generously, to give to our Commerce with your Dominions; the Punctuality with which you have caused the Treaty with us to be observed…make a deep Impression on the United States, and confirm their Respect for, and Attachment to your Imperial Majesty.”

The rest of the Barbary Coast, however, proved to be much more hostile. In 1786, John Adams was becoming frustrated with his negotiations with Algiers, as Algiers was not as understanding as Morocco of the US’s financial difficulties. Adams was disturbed that the US needed to devote resources to forging peace with a country it hadn’t even been involved with, and that paying the requested tribute would have required fresh loans from Holland.

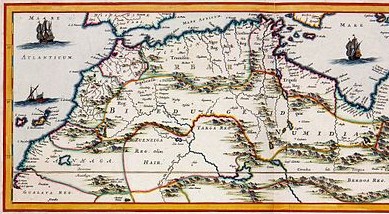

Map by Jan Janssonius. Photo: Wikipedia Commons

After several years of failure to complete treaties with Algiers and Tripoli—or to secure lasting protection from European powers—the US began to consider creating a naval force to protect US commerce, a subject which had been controversial at the time. Secretary of War Henry Knox eventually called for building a navy specifically to punish the Barbary States. In 1794, Congress passed the Act to Provide Naval Armament, legislating the building of six frigates. Still, a stipulation required that construction be halted upon approval of a peace treaty with Algiers, demonstrating the limited scope of this new naval force in the eyes of the US Government.

Despite this limited intent, the construction and development of the US Navy, spurred by these complicated entanglements in North Africa, put the US in a much better position for its later naval battles. These conflicts demonstrated to the hesitant US Government that a standing Navy was a necessity and prepared it for the larger battles to come. Besides the Barbary Wars, the nascent US Navy would clash with France in the Quasi-War (where it engaged French forces in the Caribbean from 1798-1800), and of course with England in the War of 1812. By then, the US Navy was well on its way to becoming a preeminent force on the seas, having honed its skills in the Mediterranean and built three world-class frigates (the USS Constitution, President, and United States).

Much of the detail behind this story was provided by “A Clash of Maritime Cultures: The U.S. Navy vs. the Islamic Corsairs, 1783-1816” by William S. Dudley, Ph.D