Updated

Western Sahara: The Trouble With Peacekeeping–However – Robert M. Holley

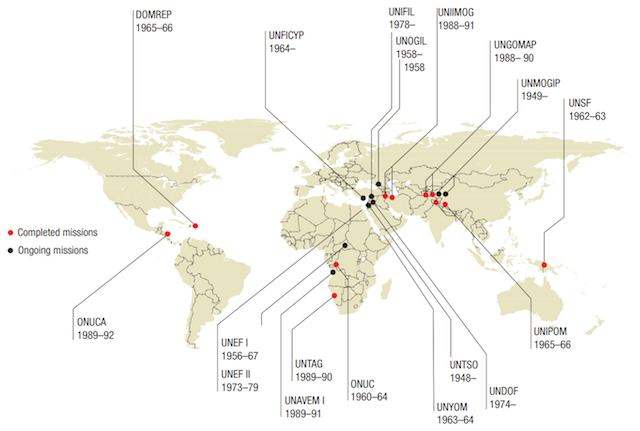

UN “Peace Operations” during the Cold War (1949–89) Photo: UN Department of Public Information

Robert M. Holley

May 16, 2019

Robert M. Holley, Senior Policy Adviser, MACP

MINURSO is not the oldest UN peacekeeping mission. That distinction belongs to UNTSO, the peacekeeping operation headquartered in Jerusalem and UNMOGIP based in disputed Kashmir along the India/Pakistan border region. These two missions have been around for more than 70 years and are among six such missions that Ambassador Dennis Jett, currently professor of international affairs at Penn State University, describes as classical peacekeeping operations in an article titled “Why Peacekeeping Fails” published in the current edition of theForeign Service Journal.

Ambassador Jett notes in his article that there are currently 14 active UN peacekeeping operations that employ nearly 100,000 soldiers at a cost of almost $7 billion annually. Ambassador Jett is an expert on their operations and his book by the same title is now in its second edition. In his article, Ambassador Jett suggests that all six of the classical peacekeeping operations are destined to fail in the sense that they are unlikely to succeed at converting the peace into a solution to the underlying problem and he recommends that they should either be abandoned or the cost of their continuance should be passed on directly to the Parties involved in the dispute if they choose to keep the missions in place.

Ambassador Jett explains in some detail why it is unlikely that these UN peacekeeping operations will end in a political solution to the various problems for which they were established. At the risk of oversimplifying his argument, what it comes down to is that rather than be seen as losing the underlying dispute, usually an issue of who owns the land in the classical peacekeeping operation, the Parties will always prefer to maintain the status quo. As evidence, Ambassador Jett notes that the six classical peacekeeping operations (UNTSO, UNMOGIP, UNFICYP, UNDOF, UNIFIL, and MINURSO) have been in existence for nearly 300 years between them without producing a solution to any of the issues involved. This is pretty compelling evidence for his premise if you accept that the only justifiable goal of a peacekeeping operation is to resolve the underlying political problem. But is that really the only, or even the most important criteria for judging the efficacy of these admittedly costly operations? What about their less obvious benefit of simply helping to keep the peace?

Of the six classical operations (Middle East, Kashmir, Cyprus, Syria, Lebanon, Western Sahara), renewed hostilities have broken out periodically in four of the examples. Only Cyprus and Western Sahara are examples where a UN peacekeeping operation has succeeded in helping prevent a renewal of active, sustained armed conflict. Does this mean that even on that basis that UN peacekeeping fails to accomplish a meaningful and important purpose? Intellectually, the argument clearly has merit supported by evidence. But so does its counterpoint.

The real question is whether removal of the peacekeeping mission is of neutral value to the prospect of renewed hostilities or whether the removal would increase the likelihood of further armed conflict. There is not a unitary reply to this question. Each case presents its own circumstances and should be judged on those alone. Making such judgments requires a deep understanding of the circumstances involved in each case. In some cases, perhaps the answer is “no, the removal would likely have no effect.” In others, it is very likely “yes, removal would likely enhance inherent instabilities and increase the prospects for further violence between the Parties, whether through willful choice or inadvertent escalation.”

My argument has been that the primary purpose of MINURSO is not to resolve the underlying political issue of “who owns the land,” but rather to give the Parties a good reason not to renew hostilities through inadvertent miscalculation as they escalate their rhetorical battles and associated military posturing in the “neutral zone” over the fundamental political dispute. This has been the basis of my discussions about MINURSO with colleagues both in and out of government over the last two years in which the mission has come under increasing pressure to accomplish a goal for which it was not created and over which it has little leverage.

The failure to resolve the underlying political issue over who is sovereign in Western Sahara is not a failure of the MINURSO peacekeeping mission. Rather, it is the collective failure of the Parties to find the political will to reach a mutually acceptable political compromise, and of the Security Council, and its most influential members with a stake in the outcome.

I will say it again, unless or until the Security Council and its most concerned members show the leadership to define the terms they use repeatedly, terms like compromise, pragmatic, realistic, and sustainable, it is highly unlikely that the Parties will have any incentive to abandon the status quo for the great unknown.

In the meantime, MINURSO continues to make a significant contribution to maintaining that status quo, which is, after all, still highly preferable to a renewal of armed conflict between Morocco and its neighbors which runs a not insignificant risk of spreading into an already highly unstable security situation in the Sahara/Sahel. That should be reason enough to keep this mission in place.