Updated

A Page in US-Moroccan Military History: Interview with US Air Force Navigator Bob Brown

Jordana Merran, MAC

March 30, 2015

Jordana Merran is MAC’s Director of Media.

Morocco and the United States have a long history of military cooperation. One might even argue that it was security concerns that first initiated the more than 200-year-old relationship: the newly-independent colonies, having lost the protection of the British naval fleet, turned to the Kingdom of Morocco for protection from the Barbary pirates, who threatened US ships in the Mediterranean Sea.

Roughly 150 years later, from January 14-24, 1943, Morocco hosted the famous Casablanca Conference, “a meeting between U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill in the city of Casablanca, Morocco.” It was at this meeting that Allied forces finalized their “strategic plans against the Axis powers” and agreed on a policy of “unconditional surrender.”

But activity did not end with the close of World War II, as Robert “Bob” Brown can attest to.

Marrakech Launching Pad

Originally from northern Michigan, Bob was a member of an aerial refueling squad in the US Air Force’s Strategic Air Command, which “served as the bombardment arm of the US Air Force and as a major part of the nuclear deterrent against the Soviet Union between 1946 and 1992.” He joined SAC in 1954, and at the time, he says, the command “was just scooping up tons of people because they had just been through the Berlin blockade, and they were looking to build up the Air Force.”

“World War II was over, and they pretty well had wiped up a whole population of Americans,” he says, “So when the Korean War was coming up and they were trying to build up the Air Force, it was old guys, probably 28 or 29 years old.” Bob was 23 when he joined.

Though the command controlled most US nuclear weapons, as well as the planes and missiles delivering those weapons, “SAC weren’t able to fly to Russia [all the way from the United States], so [the Americans] talked to the French and got permission to build four airfields in Morocco. They ended up using only three of them, including Ben Guerir Air Force Base —about 36 miles north of Marrakesh.”

In March 1956, Bob and his crew flew from Maxwell Air Force Base in Alabama to the Azores islands; and from there arrived at Ben Guerir.

“What does a guy from the Midwest know about Africa?” asks Bob. “Well, nothing. And we came in [shortly before] Ramadan. How many guys know about Ramadan? Nobody. So we got our instructions.

“[US Air Force General Curtis] LeMay was very careful not to offend—he had a bad name, he was parodied during the Vietnam War—but he was very conscious of others people’s feelings so we all got instructions on Ramadan. We were warned that on base the workers that were recruited from the local population might be sleepy, they might be fidgety, they might be anything—but be sure that you take into account that this is their religious period and it’s very sacred to them.”

Getting to Know Morocco

By this time, the French had already exiled Sultan Sidi Mohammed ben Yusef, and tensions between the Moroccan population and French colonizers were high. (Indeed Morocco now commemorates the day of Sultan Sidi Mohammed ben Yusef’s exile as “King and People’s Revolution Day,” because it marked a turning point in the movement for independence.) The Americans were warned to “wear a full uniform at all times” and not to go into the medina or the cafes, because locals would not be able to distinguish between French and American servicemen, Bob remembers.

Of course he and many other American servicemen couldn’t resist exploring. “They finally found a worker off of the base to drive us into town,” he says, and he and his buddy Nelson “Nellie” O’Neill perused the shops of Marrakech.

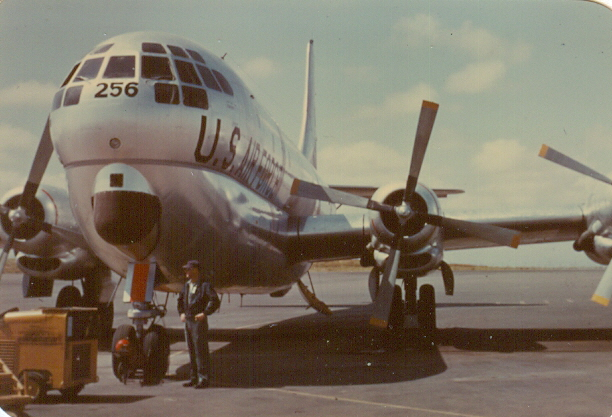

KC-97 F on the flight line at Ben Guirer in 1956. Photo credit: Bob Brown.

“Nellie wanted to bring back one of those big brass trays to make a coffee table out of it; that and camel saddles,” recalls Bob. “When you went downtown to shop, people were always trying to sell leather goods. They would go after Nellie and he would go after these big tray things. They’d say 500 dollars and he’d say ‘no, no, no’ and they’d keep [bringing the price] down. When it got down to coming home he paid them 200 dollars for it.”

Relations between the Americans and Moroccan locals were good, says Bob, remembering the Moroccan staff member assigned to his Dallas Hut (a temporary barrack). “I thought, ‘Here I am a college graduate and here’s a guy that speaks French, Arabic, and English and was pretty fluent’; he was teaching us a bit of Arabic and I was thinking, ‘Isn’t this amazing?’ I have no idea what his political affiliations were, but we didn’t care: he was our guy, and we took care of him and fully trusted him, and he took care of us.”

Shortly before the end of his stay in Morocco, the French allowed the exiled Sultan to return.

“[US command] told us one day that ben Yusef is coming back, and they said during this period of time to not go out on the highways, to stay on the base. People will be walking for miles and miles, they explained, because ben Yusef was extremely popular.”

Bob describes it as “the first break.”

“The French decided that they couldn’t fight anymore and that they would make peace [by bringing back ben Yusef]. There was peace, but the Moroccans wanted independence. Things weren’t good. Within a short period of time was the end of French rule.”

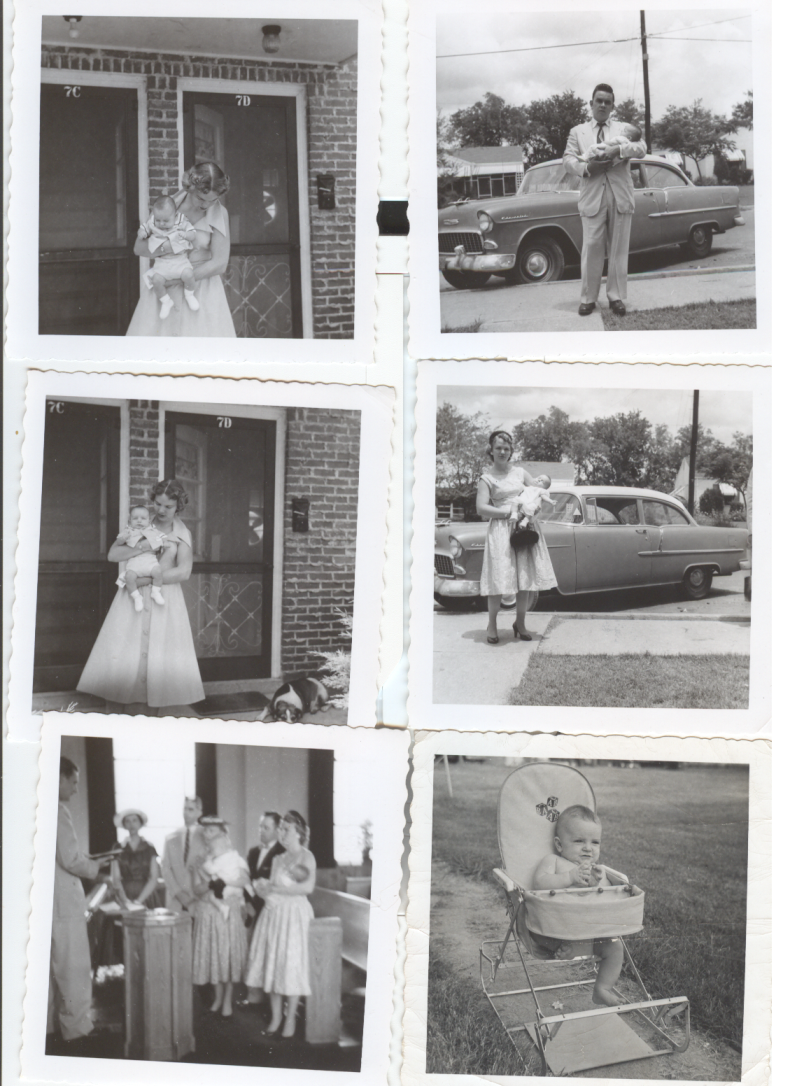

A New Father, a New Chapter

Just minutes after landing at Ben Guerir, Bob had been informed that his wife had given birth to their first child back at Maxwell Air Force Base. She had been due April 8, and needless to say the news came as a surprise. But Bob had to wait until the next flight back on March 28 and train a replacement crewmember in the meantime.

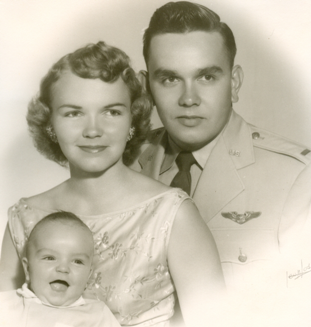

Bob Brown with his wife Gail and their 4-month-old son, Mark in 1956. Photo courtesy: Bob Brown.

“When you were assigned an airplane,” explains Bob, “You went in as a crew, you checked out as a crew. You washed the airplane together, you did everything together as a crew.”

As luck would have it, though, the March 28 flight left without him. A B-47 plane had disappeared during a routine flight, and with the baby already more than two weeks old, the Air Force figured he might as well stay longer to assist in search missions.

He remembers flying one such mission over the Sahara desert. “We came over a dune and saw people gathered around a little oasis. We scared the stew out of them and they scared the stew out of us!”

Ultimately, they never found the B-47, and Bob wouldn’t meet his baby boy until May, when he was already 67 days old. When Bob’s Air Force contract was up, his wife urged him not to renew.

More than forty years later, in 1999, he came across an article in the New York Times by Joseph Gregory that grabbed his attention. It was an obituary of King Hassan II, the son of ben Yusef. “It was a great piece as far as [describing] the [history]. The names popped out at me, I really [had remembered them].”

The memories of what he calls a “fantastic experience” in Morocco.